If it’s not obvious already, one of the major parts of my work with the Internet Archive involves going after those very subjects, items and collections that would fit perfectly within its hallowed walls but which nobody with the items, or archive.org, has made the connection. I’m the connection. And I’m connecting.

A lot of my recent effort has just been learning the archive.org back-end, which is a little strange but very geared towards keeping things around forever. A lot of machines do a lot of tasks, and attempts are made to give you a lot of options to get things out of the “stacks”. It’s really, really good for books and documents, which was the first primary item the site had after webpages – you can get versions of documents for reading online, downloading in PDF form, pulling into your Kindle or what have you. Music, also pretty good. Video? Working on it, getting better all the time (just this past week, more options for video showed up). Ironically, this is the opposite approach to pretty much all commercial sites that harbor media – they all hide the original and show you derivatives. Archive.org ensures you always can get the original and does its best with derivatives. So learn this system I have, and the learning continues.

Here, then, is my newest collection to present, one that has had a personal side and interest for many years: The Hardcore Computist Collection. Everything I’m going to say is to give context of this collection and how things got to where they are, so feel free to just go ahead and click that link and while away an afternoon.

As things shake out and the Apple II becomes a footnote to the contemporary world that thinks of Apple as a music and exotic hardware design company, I think it’s a great idea to capture as much of that earlier machine’s history and related culture before it all flattens out completely. The Apple II had a huge following for the time, is still being used for experimentation and fun, and continues to amaze and delight with the simplicity of its approach combined with the complexity of the ideas it inspires. To the goals of preservation, there’s a lot of scanning, interviews, software and hardware being assembled to capture it. I’ve been involved in some of that, but I’m a tiny, tiny needle in the haystack of all these folks. What I’m mostly good at, I guess, is bringing attention to aspects of this effort and bringing them the visibility and regard they deserve.

So it goes, then, with Hardcore Computist, one of the more amazing things to rise out of the wild success of the Apple II and industry and customer base around it.

It was, depending on who you talk to and in what context, a blow for computer users’ rights far in advance of issues twenty years away, or a software pirate’s journal, or a strange technical magazine dedicated to the liberation of understanding about the software being written for this amazing home computer. It might be all of them. What it unquestionably was, however, was a professionally printed magazine dedicated to removing copy protection schemes from commercial software for the Apple II.

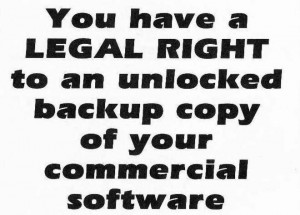

The opening issue of the first incarnation of the magazine, Hardcore Computing, lays it out straight. The magazine, says publisher Charles R. Haight, is a salvo in a battle, a silent battle between the “establishment” Apple II magazines, and the users. The users, you see, had been stripped of the right to legal backups of their software, software they bought, and even though strides were being made to allow users to de-protect and duplicate their copies, magazines were refusing to write about this or publish ads for tools to help said users. This, to Haight, was censorship, plain and simple, and Hardcore Computing would fix that.

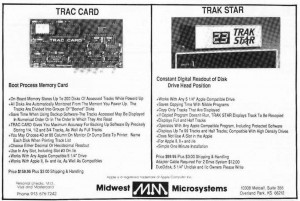

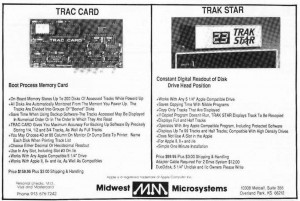

What followed is ten years of amazing publishing – dozens of issues, all written clearly, stridently, and never turning away from the nuts and bolts of hacking away at software programs to tame them and make them do what you want. It is, in many ways, a very beautiful work, with minimal but striking artwork (horses and space seem to be a recurring theme) and the occasional single-color paper tint. Over the years, color does make an appearance, but as the Apple II’s fortunes fade, so does Computist’s and the magazine shifts down to a newsletter, and then ultimately some scattered galley proofs of issues never published. It had several names, multiple focuses, and oh man, the ads. It’s worth it just for the ads.

That I know about this magazine, and that people were able for years to read this magazine online, was the work of one Mike Maginnis, who scanned all the copies of the magazine to the best of his abilities and began offering the images from these scans online, through a variety of sites. After finding out about his work, I mirrored it on textfiles.com, with a different interface, but didn’t add much of anything to it, and frankly I had it looking pretty and absolutely worthless for browsing. Fast forward, then, and I have taken the latest revisions of Mike’s scans and put them on archive.org to make permanent. Mike was all for it.

While I know the collection is not 100% complete, and some scans are fuzzy, this is an important step in the right direction – the issues are now protected under the auspices of a library, and can be checked out by anyone who wants to head over there and read them online, or download the original PDFs, or anything else that might grab their fancy. It provides, along with Mike’s site and collection, a non-profit registered-library home dedicated to its preservation, and that’s pretty darn cool.

To help with the entering of descriptions and metadata about these issues, I called out generally and a bunch of people answered the call. So please, a very big thank you to Heather Bowden, Louise Pichel, Lewis Collard, and Colin Djukic, who downloaded issues and typed out a bunch of relevant information so these issues would catch into search engines and make the future patrons of this library happy with how easy it is to find something.

This doesn’t mark the end of preserving Hardcore Computist and its related publications, though – it’s just a new stage. I’ve given it a new platform to thrive, but it won’t thrive without contributions from other historians and collectors who know a lot more about this world than I do. I’d love to see items added, descriptions puffed out, better replacement scans over time for items that could use them. It’d be a great blow against the tides of entropy and amnesia that affect all things now made, in many ways, obsolete or seemingly so.

Enjoy the read. And back up your software!

4 Comments