In Which My Situation is Discussed. —

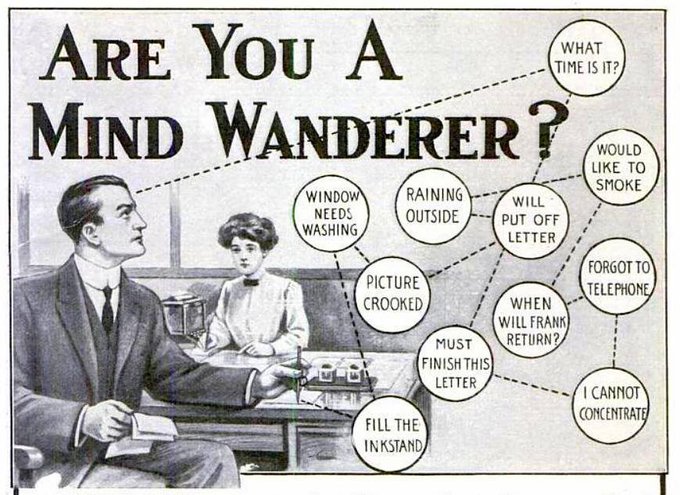

Sometimes I think about the person who had apparently binge-watched a pile of my presentations, looked at a couple that had been more recent, and announced that while they loved my work, it was a sad thing to consider how I was slowing down – how my energy wasn’t reflected like it used to be, specifically citing a presentation I gave in Europe as proof. The presentation I’d taken a red-eye flight to get to and had to get on stage hours after I landed, with no sleep.

There’s a wide gap, in many facets, of the presentation of myself that I put online and the life I live and have lived day to day. My hope is the most interesting aspects are seen by a public that enjoys my company, and not seen by people who find me a grating somnambulance in an online life they’re just trying to get by in.

But regardless, mythology continues to rule the day.

At some point in the green days of Twitter as the world’s chatroom, I was mentioned and, because my handle found its way into searches, a collection of people I’d blocked over years discovered they all shared this trait. They began talking amongst themselves, trying to discern why I’d done such a drastic thing. While they never quite stumbled onto the beach of the actual obvious reasons I had, they did in fact swim about and cook up a fascinating answer: I was beginning to develop a mental breakdown and possibly one of the degenerative brain diseases, and in doing so my personality had changed, and I wasn’t there anymore. This conclusion worked gangbusters for me, because then the trash takes itself out. I’ve got Hackerzeimers. Go with that.

It’s not difficult to get relatively known for something, if you do it a lot, and talk about it. If you’re both lucky and persistent, it might grow to something beyond that. It is odd for an outsider cataloguer and enraged librarian to gain anything resembling a following of sizeable mass, and if the fan mail is any indication, a warm spotlight of affection as I drift in and out of peoples’ awareness. I’ve been lucky or damned.

All this to say that, while I’ve certainly benefitted from an elevated profile for what would otherwise be a series of simple and repetitive vocations and hobbies, the road to glory has not been devoid of bumps and bruises. Most of these have been minor, a few clearly not. As my records show I’ve written essays on this weblog less than a dozen times in the last few years, whereas I once tried doing them nearly daily and at least weekly, and the result is that for some people, devoid of knowlege of me personally, might assume my star has fallen or I’m lying on my side on a day bed asking the staff to play my greatest hits on a screen nearby.

This, fundamentally, is a direct cause of how exactly people are keeping tabs on me. I can assure everyone of several basic facts, some of which I can expand on, but which might stretch the level of your interest in knowing:

- I continue to be extremely healthy in a cardiac way – my prescription regimen and no longer having a propensity to make tuna melts an unveering pillar in my diet, along with generally seeing doctors at the beginning instead of towards the end of a condition, have kept me quite fine.

- I do a podcast episode every single week and I’m officially at 350 episodes. The Patreon is where you will hear them and I eventually get around to syndicating them to the general public; but the Patreon gets them first. By a rough back-of-calculator-app estimation, I have nearly 3 full days of audio of me talking about myself, issues and the general state of the past and current world.

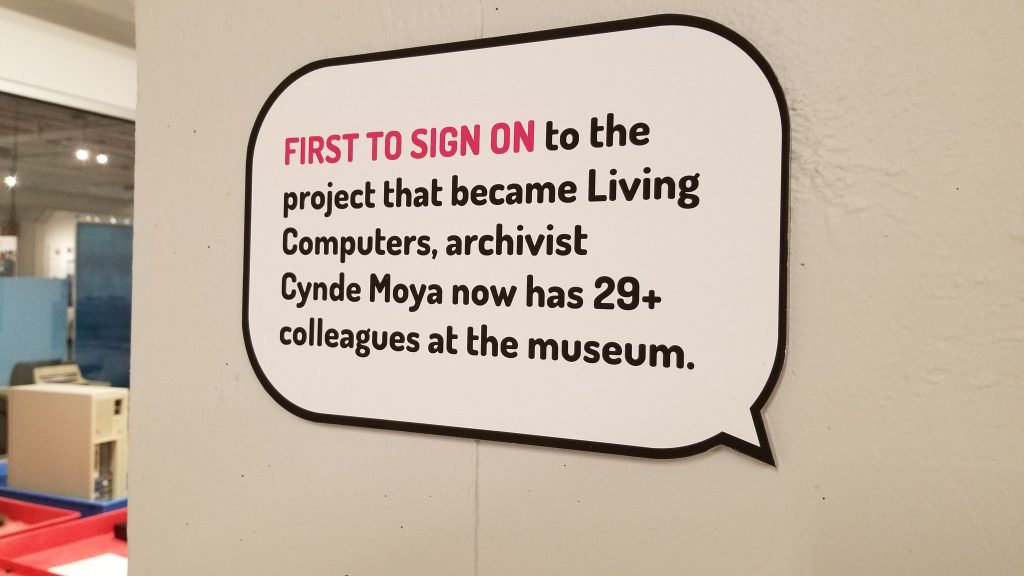

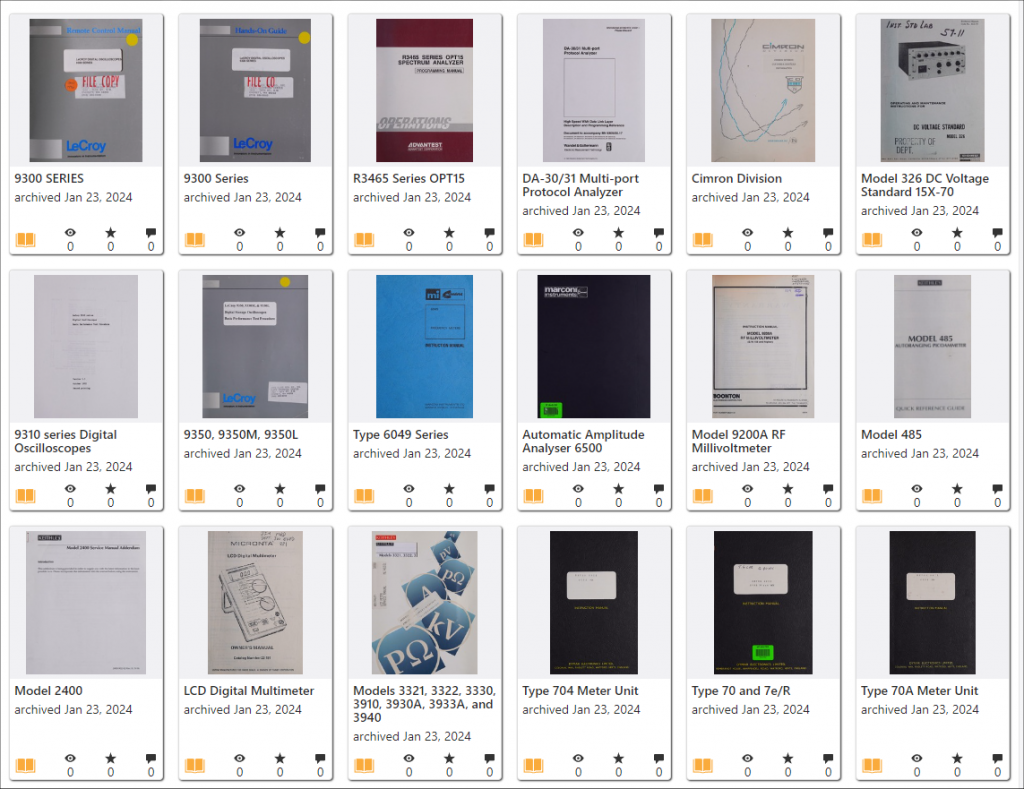

- Early next year I will celebrate 15 years at the Internet Archive, making it my longest single run of employment. I do not truly have a saying in the matter but I would not mind a world where it was my last job altogether. I read this article and I am inspired.

- I have been to a sizeable amount of locations both domestic and international and I’ve attended hundreds of movies, concerts and events, preventing any sort of regretful wail from where Montressor has chained me.

- This past year, I acquired a persistent stalker, harmless but ambiently entertaining, and, in a plot twist, an entirely different person attempted to get multiple family members and myself killed. They were, ultimately, unsuccessful.

In short, there’s nothing too much to worry about.

The rest of this entry is neither announcement nor attack. It’s mostly me talking about a really wonderful outcome in terms of working space, and the financial lean it’s causing.

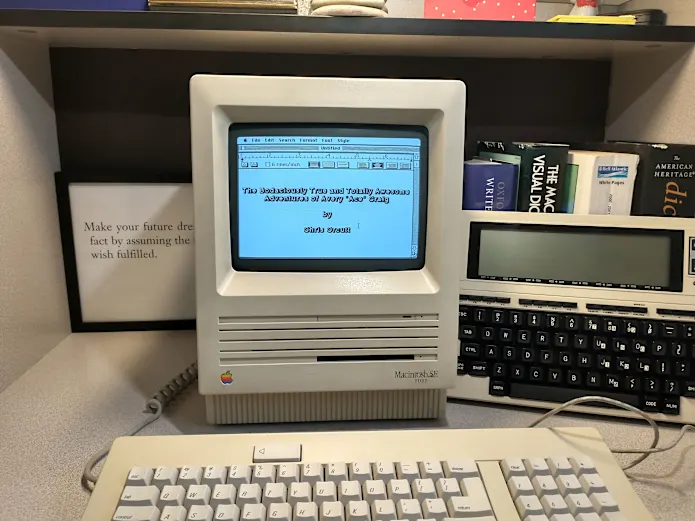

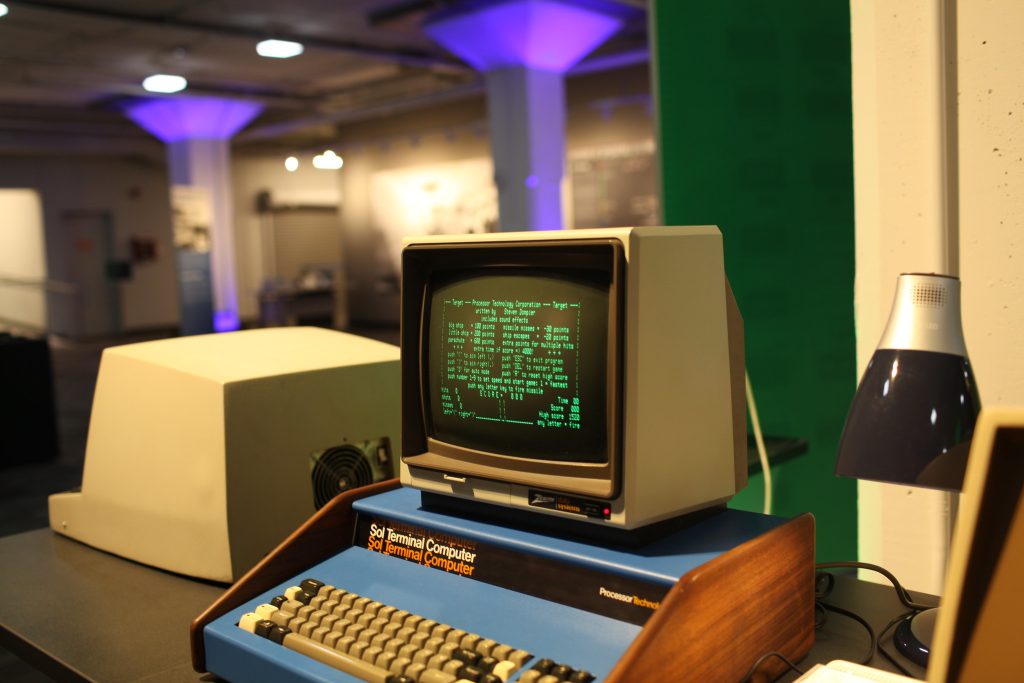

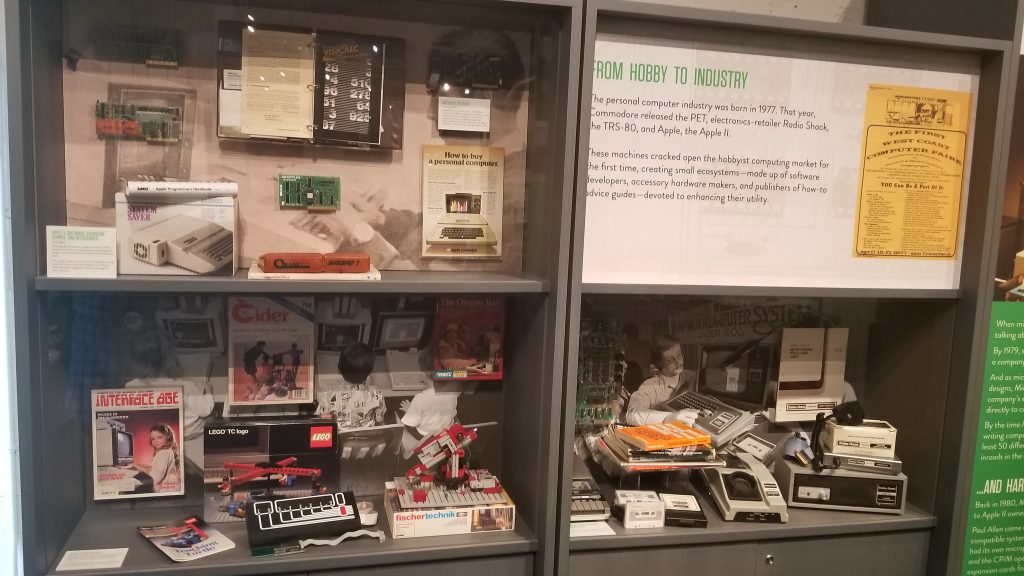

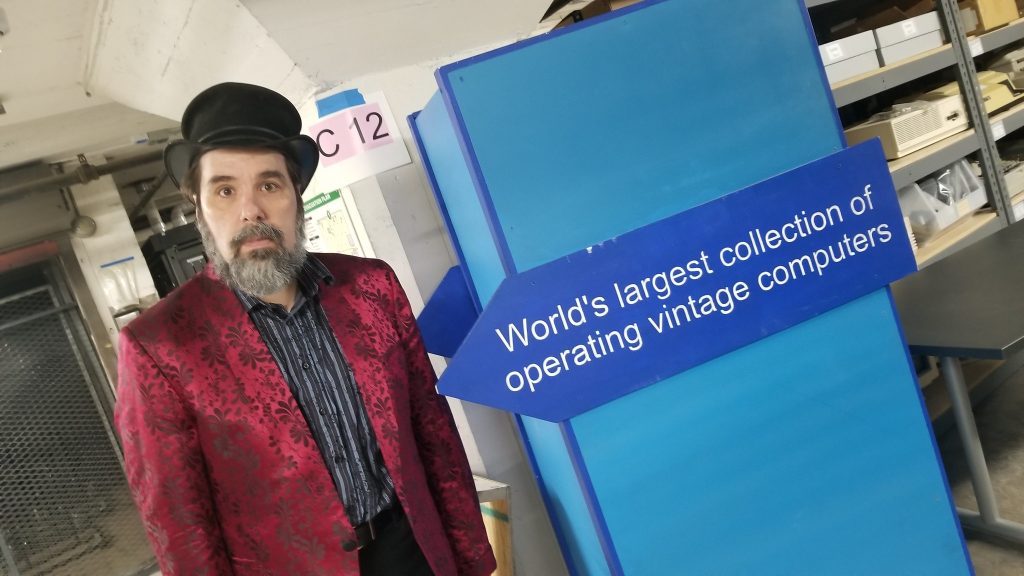

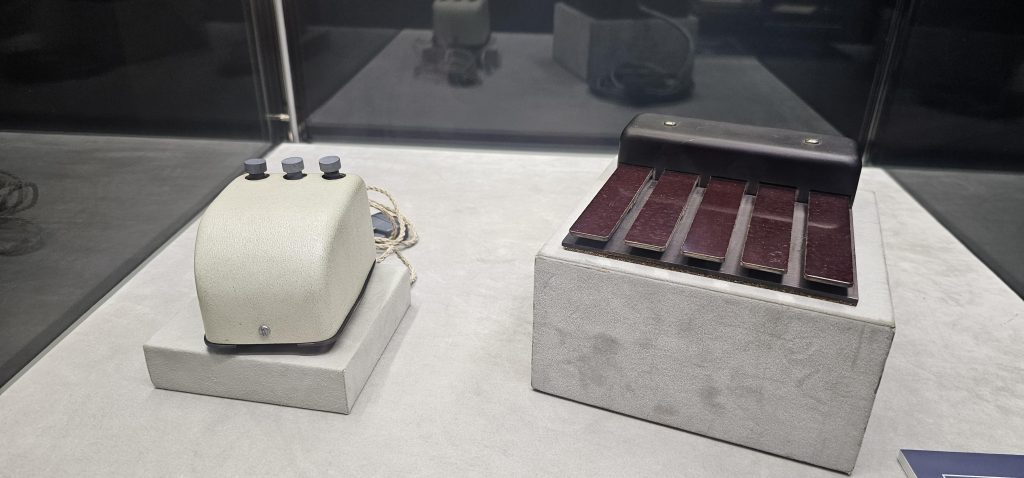

Some time ago, I cleaved my spaces in twain. I continued to live in a series of apartments, but the part of me that desires sleep, meals and a pleasant desktop machine and doesn’t want to be surrounded by the detrius of a thousand conversations would keep said apartment – but the part of me that does want to be the Willy Wonka of Crap began renting a small office.

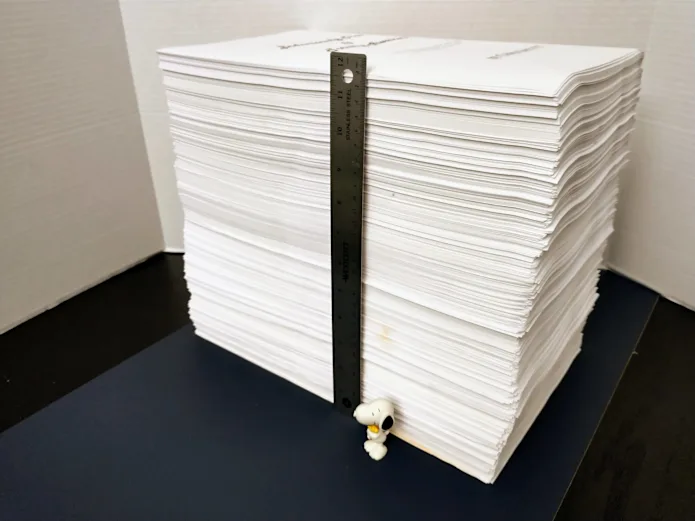

And I do mean small – 90 square feet, although with some camera trickery I could make it seem like more. Photos from this space range from sadly quiet to artistically fun.

It was exactly what I needed. Near my apartment (a walk, really). Confined only to the worlds of digitization, livestreaming at loud volumes, and getting on with it as regards my archive work. And, relatively, it was inexpensive.

That said, inexpensive is not zero expense, and I was lucky enough to be subsidized by a number of people, most notably the awesome FaxZero company. Between all of this, my costs were notable but quite under control. A lot of work was done in this office – thousands of items digitized, thousands of mails answered, interviews and presentations conducted.

Over time, the management company behind this small office, who also provided a meeting room set (which I only used twice) and appliances (which I wandered out to occasionally) would raise the rent here and there. Still – in general, I felt very safe, especially what with the threats and the occasional demands to meet me in person to Settle Things. I could walk in past a security guard setup, go up a few floors, and go into my favorite type of world – a windowless room. It turns out I really like working inside a dark box, and while more expensive offices provided windows and outward facing doors, my love of a tiny alcove with minimal light worked out for me – for a few years.

As is often the case, this management company raised its rent, usually a small amount, occasionally a leap, until the cost they were charging for my little box was past $100 a square foot. I had to decline a renewal of the lease, and move onwards.

As is also often the case, this seeming upheaval instead provided a truly wonderful opportunity.

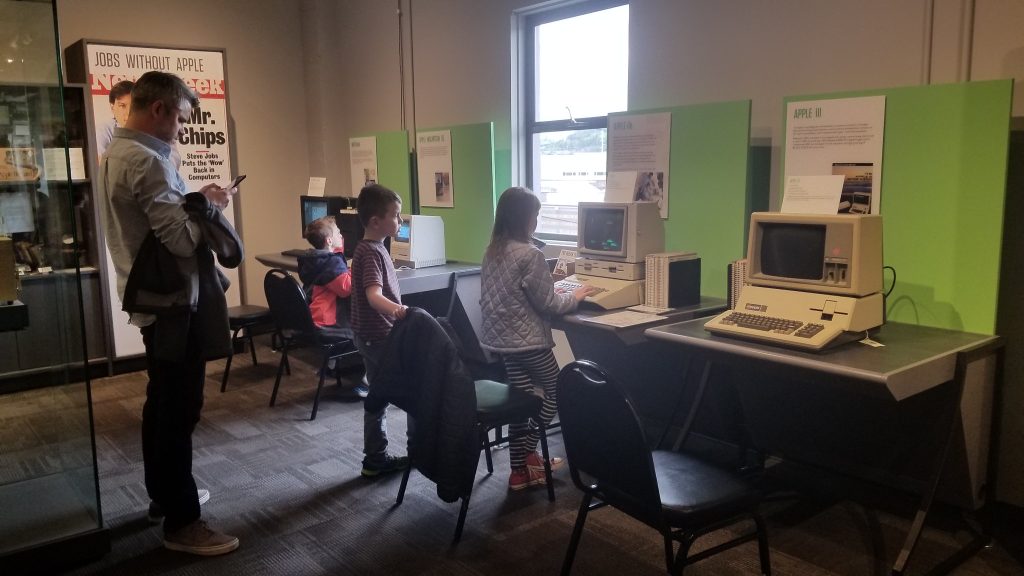

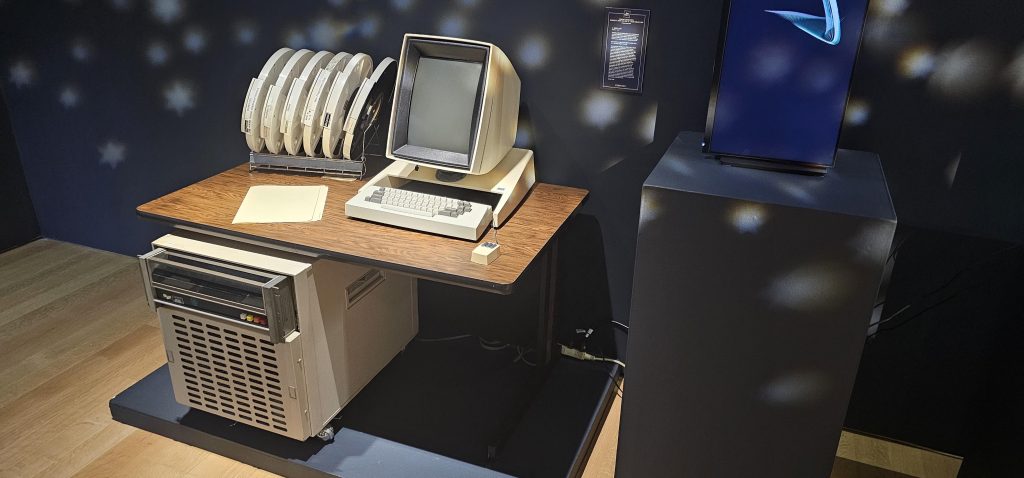

Casting around for a new place to rent, I decided to go for it and just pursue industrial listings and spaces. The differences between this, and, say, simple rooms or professional shared office space deals, is that you can get some absolutely whacky listings: unfinished warehouses, empty storefronts, buildings with strange and unusual tenants and somewhere deep inside, a room with your shingle on the door.

That’s how I found my current space – looking for unfinished warehouse space with the rough plan of pitching an industrial canvas tent inside and having my materials inside like a warped meth lab, I instead took a really engaging tour with an absolutely charming and fair-dealing landlord. We looked at more reasonable options and came to terms almost immediately.

Here is what comes of not settling and taking a leap into the unknown.

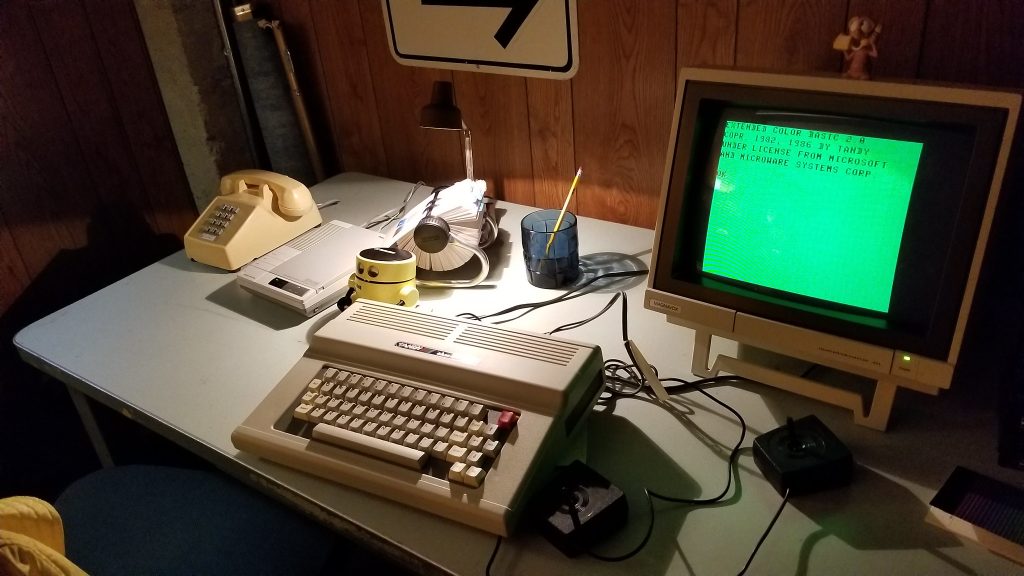

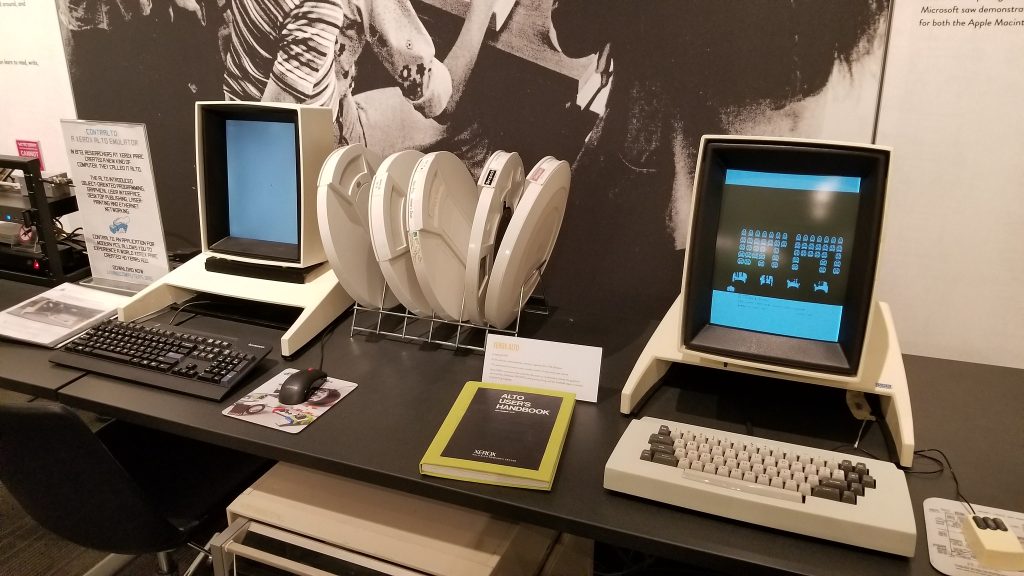

I hope it’s obvious what a truly revolutionary situation this is for me. The reason there’s so much more in this room is because I was able to 100% clear out every single paid-for storage unit and home-based pile of anything related to my archiving and digitizing work. It’s all in one room. That alone is a major relief.

It’s lit like a nightclub because I like indirect colored lights, and I can go wild in there.

And within this location, I livestream my archiving/working days, go through long-dormant promises and plans, and have been aggressively digitizing or disposing of “what next” items I’ve had with me forever.

Dozens of boxes have left this room. Every photo, including the one above, is out of date within a few days of taking it, as items are processed, repackaged, cleared out, and sent away.

It is, in many ways, a culmination, a heavenly moment, a true beloved space.

This should be the end of it, of course – just a note that I’ve moved, like a basic birthday announcement or a declaration that we made it, folks. I should be spending my hours a day digitizing and getting materials up by the terabyte to the Internet Archive and other destinations, moving this backlog out at the major speeds I’m currently achieving.

But.

After the initial year, my rent went up for Bank Reasons. My landlord walked me through the entire financial reason, including an anchor tenant moving elsewhere, and an audit by the financial instituion that is co-owner of the property, and my rent now stands for the next few years at $1000 a month.

I have a solid income. I absolutely can continue to pay this unabated and will do so.

But over time, various folks have thrown me funds to help with this burden (as well as costs of hosting, and other aspects of what I suppose constitutes my public life). There have been months I’ve borne the whole cost of these various recurrent debts, and months I’ve not paid anything. The uncertainty is beginning to have a toll.

So I’ll say:

There are a variety of ways to support this space that sends out so much material, ranging from sponsorship of the livestream, sending money to me via the paypal or venmo services, or signing up for the Patreon. If you have means and wish to help contribute towards that, it would be very welcome. My e-mail and other points of contact are open.

Otherwise, and I seriously have to stress this:

Nothing will change. If you’ve given me funds and support in the past, nothing is going behind a new paywall (and I thank you profusely for that past help). Nothing is going to be stopped, nothing is going to end. I’ll continue what I’m doing to cobble together the budget, and it inspires me every day I go to the office to make the absolute most of that space and use the equipment and tools within it to work at the top speed I can.

It’s been a wild ride to get here, and it will continue. See you on the stream.